ARTICLE

Some constellations in the Western sky have been gone over time.

I. Two perspectives

Until 1922, the year astronomers agreed there were 88 constellations in the sky, the stars had been represented in several ways throughout centuries. In Western classic depictures, they were mentioned as being part of mythological patterns, which became the usual way to allude to them.

Many cartographers considered Claude Ptolemy's stars catalogue Almagest from the middle I c. b.C. as the base for their works, a document that included observations made from the Greek Mediterranean Sea. The cartographies depicted the stars mostly as seen from Earth, although Albrecht Dürer's charts (1515), Peter Apian's astrolabe (1540) and Johannes Hevelius' atlas (1690) were exceptions, since they represented them as seen from space, like celestial globes do. Dürer's works were also distinctive since were the first ones to display the Milky Way path, and even on charts seeming the current way to draw Western astrological birth charts: the Zodiac was placed around a rim (the center was the celestial pole on the maps), counter-clockwise, and dividing the whole area into 30° segments.

II. Changes in mapping

The catalogues were based on registries made from different locations on Earth, like the Mediterranean Sea, Greenwich (England), Shīrāz (ancient Persia in Iran), Madagascar and Cape Town (Africa), Sumatra (Asia) and Saint Helene islands (Atlantic Ocean). The astronomers didn't just updated the positions but also included more stars, what made them introduce new constellations to include them. However, not all of the astronomers approved those ones created by others, and sometimes they didn't depict them in their atlases.

With or without recognition, the Earth's axis motion always changes the view of positions, which is better noticed as centuries pass by since one observation until the next one. So it seems some stars are "getting closer to" or "moving away from" each other, a seeming change making cartographers relocate them in other constellation, which made disappear some patterns whereas new ones were created. Another reason to change their constellation was to avoid overlaps as other stars were added.

Mythological drawings were the main reference although some cartographies progressively included more elements to identify stars with greater accuracy. For example, there were mentioned before Dürer's radial lines at 30° intervals, whereas Johann Bayer was the one who assigned Greek letters to stars in the XVII c. to indicate brightness, and depicted them on grid plates with calibrated margins to specify degrees. In the following century, Alexander Ruelle linked them with lines. In the XIX c., Johann E. Bode registered by the naked eye more than 17,000 stars in over 100 constellations, and also drew soft boundary lines between them. Finally, at the end of the same century, the Belgian Eugène Delporte traced zigzag boundaries for making the stars stay inside of the constellation they were assigned to, according to their declination and passage across the meridians, leaving definitely behind mythical patterns as references, and now setting definite areas.

indexIII. Lost constellations

From ancient mythological narrations to current mappings based on brightness and mathematical calculations of exact positions, many centuries have passed by and many efforts have been made to take notes, transmit and preserve catalogues and representations. This article displays some of those ones that have remained on the way, not being part anymore of the now recognized 88 constellations. They are 17 constellations introduced here in the order they were created, between the XVII and XIX centuries, related to myths and also to objects, animals and famous people by those times. The cartographies belong to different authors (not necessarily to the inventor of the constellation), so the works and years mentioned below refer to the cartographer. Touch the blocks for brief descriptions.

IV. The 88 constellations

Current constellations and main stars

| # | name | creation | location | stars |

| 1 | Hydra water snake (female) | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S/Eq (South Cancer and Leo NH, and North Virgo, Libra and Scorpio SH) |

|

| 2 | Virgo virgin | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | Eq |

|

| 3 | Ursa Major great bear | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Leo) |

|

| 4 | Cetus sea monster | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | Eq (South Aries and Pisces) |

|

| 5 | Hercules strong man | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (South Draco, in Sagittarius' parallel) |

|

| 6 | Eridanus river | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S/Eq (between Taurus NH and Fornax SH) |

|

| 7 | Pegasus winged horse | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Aquarius SH and Lacerta NH) |

|

| 8 | Draco dragon | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between the North Pole and Hercules, parallel to Scorpio) |

|

| 9 | Centaurus . | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (between Hydra and Crux, in Virgo's parallel) |

|

| 10 | Aquarius water bearer | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S/Eq |

|

| 11 | Ophiucus serpent bearer | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | Eq (between Scorpio SH and Serpens NH) |

|

| 12 | Leo lion | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N/Eq |

|

| 13 | Boötes herdman | s. XVII (Hevelius) | N (North Virgo) |

|

| 14 | Pisces fishes | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N/Eq | |

| 15 | Sagittarius archer | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S |

|

| 16 | Cygnus swan | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Vulpecula and Cepheus, in Capricorn's parallel) |

|

| 17 | Taurus bull | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N/Eq |

|

| 18 | Camelopardalis giraffe | s. XVI (Plancius) | N (next Minor Bear, between Taurus and Gemini) | |

| 19 | Andromeda chained woman | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Pisces and Cassiopeia) |

|

| 20 | Puppis keel | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between North Volans and South Carina, between Gemini and Cancer NH) | |

| 21 | Auriga charioteer | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (South Camelopardalis) |

|

| 22 | Aquila eagle | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | Eq (between Sagittarius SH and Sagitta NH) |

|

| 23 | Serpens serpentarium | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | Eq (South Hercules, parallel to Libra) |

|

| 24 | Perseus hero | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Taurus) |

|

| 25 | Cassiopeia seated queen | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Andromeda, between Aries and Pisces) |

|

| 26 | Orion hunter | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | Eq (between Taurus and Gemini, to South) |

|

| 27 | Cepheus king | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (next to the North Pole, in Leo's parallel NH) |

|

| 28 | Lynx . | s. XVII (Hevelius) | N (between Gemini and Cancer, to North) | |

| 29 | Libra balance | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S |

|

| 30 | Gemini twins | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N |

|

| 31 | Cancer crab | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N | |

| 32 | Vela sails | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (North Antlia SH, in Leo's parallel NH) |

|

| 33 | Scorpio scorpion | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S |

|

| 34 | Carina stern | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (South Puppis, in Cancer's parallel NH) |

|

| 35 | Monoceros unicorn | s. XVI (Plancius) | Eq (South Gemini) | |

| 36 | Sculptor . | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between North Phoenix and South Cetus, in Pisces' parallel) | |

| 37 | Phoenix fire bird | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between South Sculptor and North Tucana, parallel to Pisces) |

|

| 38 | Canes Venatici hunting dogs | s. XVII (Hevelius) | N (North Coma Berenices and Virgo) |

|

| 39 | Aries ram | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N |

|

| 40 | Capricorn sea goat | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S |

|

| 41 | Fornax furnace | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (mostly surrounded by Eridanus, in Aries' parallel NH) | |

| 42 | Coma Benerices Benerice's hairs | s. XVI (Vopel) | N (North Virgo) | |

| 43 | Canis Major great dog | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (North Monoceros, in Gemini's parallel NH) |

|

| 44 | Pavo peacock | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between North Octans and South Telescopium, in Sagittarius' parallel SH) |

|

| 45 | Grus crane | s. XVII (Hevelius) | S (between North Tucana and South Pisces Australis, in Aquarius' parallel) |

|

| 46 | Lupus wolf | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (North Libra and Scorpio) | |

| 47 | Sextans . | s. XVII (Hevelius) | Eq (South Leo) | |

| 48 | Tucana toucan | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between Octans in the South Pole and South Phoenix, parallel to Aquarius) | |

| 49 | Indus hindu | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between South Octans and Microscopium, in Capricorn's parallel) | |

| 50 | Octans . | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (South Pole) | |

| 51 | Lepus hare | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (between North Columba and South Orion, between Taurus and Gemini NH) |

|

| 52 | Lyra lyre | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Draco NH and Sagittarius SH) |

|

| 53 | Crater cup | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (North Leo and South Hydra) | |

| 54 | Columba dove | s. XVI (Vopel) | S (between South Lepus and North Pictor, between Taurus and Gemini NH) |

|

| 55 | Vulpecula fox (female) | s. XVII (Hevelius) | N (South Cygnus HN and Capricorn SH) | |

| 56 | Minor Bear small bear | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Pole) |

|

| 57 | Telescopium telescope | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (North Sagittarius) | |

| 58 | Horologium clock | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between North Hydrus and South Fornax, in Taurus' parallel NH) | |

| 59 | Pictor easel | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between North Dorado and South Columba, in Taurus' parallel NH) | |

| 60 | Pisces Australis Southern fish | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S |

|

| 61 | Hydrus water serpent (male) | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between South pole and North to Reticulum and Horologium, parallel to to Aries) | |

| 62 | Antlia air pump | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (South Vela and North Hydra, in Leo's parallel NH) | |

| 63 | Ara altar | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (North Scorpio) | |

| 64 | Minor Leo small lion | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Leo and Ursa Major) | |

| 65 | Pyxis compass | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (North Hydra, between Carina and Antlia, in Cancer's parallel NH) | |

| 66 | Microscopium microscope | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (North Capricorn) | |

| 67 | Apus bird of paradise | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between South pole and Triangulum Australe, parallel to Scorpio) | |

| 68 | Lacerta lizzard | s. XVII (Hevelius) | N (between Cepheus and Pegasus, in Aquarius' parallel) | |

| 69 | Delphinus dolphin | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (between Vulpecula NH and Capricorn SH) | |

| 70 | Corvus crow | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (North Hydra and next Crater, in Virgo's parallel) | |

| 71 | Canis Minor small dog | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N/Eq (between Gemini and Cancer, to South) |

|

| 72 | Corona Borealis Northern crown | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Serpens Eq, between Scorpio and Libra) |

|

| 73 | Dorado swordfish | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between South Pictor and North Mensa, in Taurus' parallel NH) | |

| 74 | Norma scale | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between Triangulum Australe and Lupus, in Libra's parallel) | |

| 75 | Mensa table | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (South Pole) | |

| 76 | Volans flying fish | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (North Puppis and South Chamaleon, between Gemini and Cancer NH) | |

| 77 | Musca fly | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (North Crux and South Chamaleon, in Virgo's parallel) | |

| 78 | Chamaleon . | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (North Volans and Musca, in Leo's parallel NH) | |

| 79 | Triangulum triangle | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (North Aries) | |

| 80 | Corona Austral Southern crown | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | S (North Sagittarius) | |

| 81 | Caelum chisel | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (between Dorado and Orion, in Taurus' parallel NH) | |

| 82 | Reticulum reticle | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (between North Hydrus and South Horologium, in Taurus' parallel NH) | |

| 83 | Triangulum Australis Southern triangle | s. XVI (Keyser and de Houtman) | S (South Apus and North Norma, between Libra and Scorpio) |

|

| 84 | Scutum shield | s. XVII (Hevelius) | S (South Sagittarius) | |

| 85 | Circinus compass | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | S (South Vela and North Hydra, in Cancer's parallel NH) | |

| 86 | Sagitta arrow | s. XVIII (de Lacaille) | N (North Aquila, in Sagittarius' parallel SH) | |

| 87 | Equuleus little horse | 150 b.C. (Ptolemy) | N (South Capricorn SH, between Pegasus and Delphinus) | |

| 88 | Crux Southern cross | s. XVII (Bartsch) | S (South Musca and North Centaurus, in Leo's parallel NH/Eq) |

|

Ref. sup.: #1 is the widest one. Ref. location: N = North Hemisphere; S = Southern Hemisphere; Eq = Equator; in parenthesis, N - S boundaries constellations (as seen from the Equator to the pole) and main zodiacal sign on the same parallel. Ref. stars: from greater to lesser magnitude (lower than 3).

Sources: astropixels.com by Fred Espenak shares a wide range of astronomic ephemeris including several decades, space photographies and the list of 88 constellations approved by the International Astronomic Union (IAU) since 1922. Star names from www.wikipedia.org.

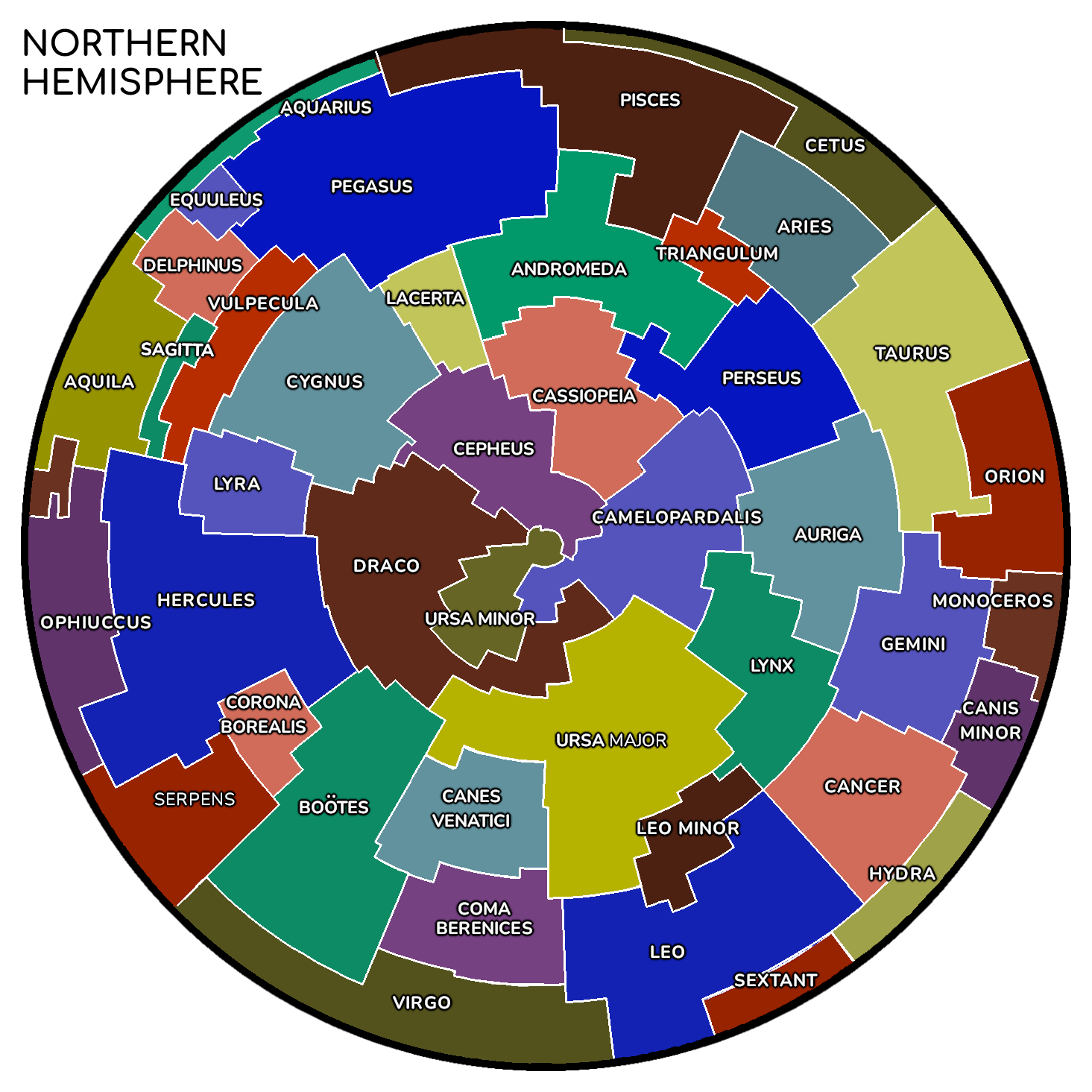

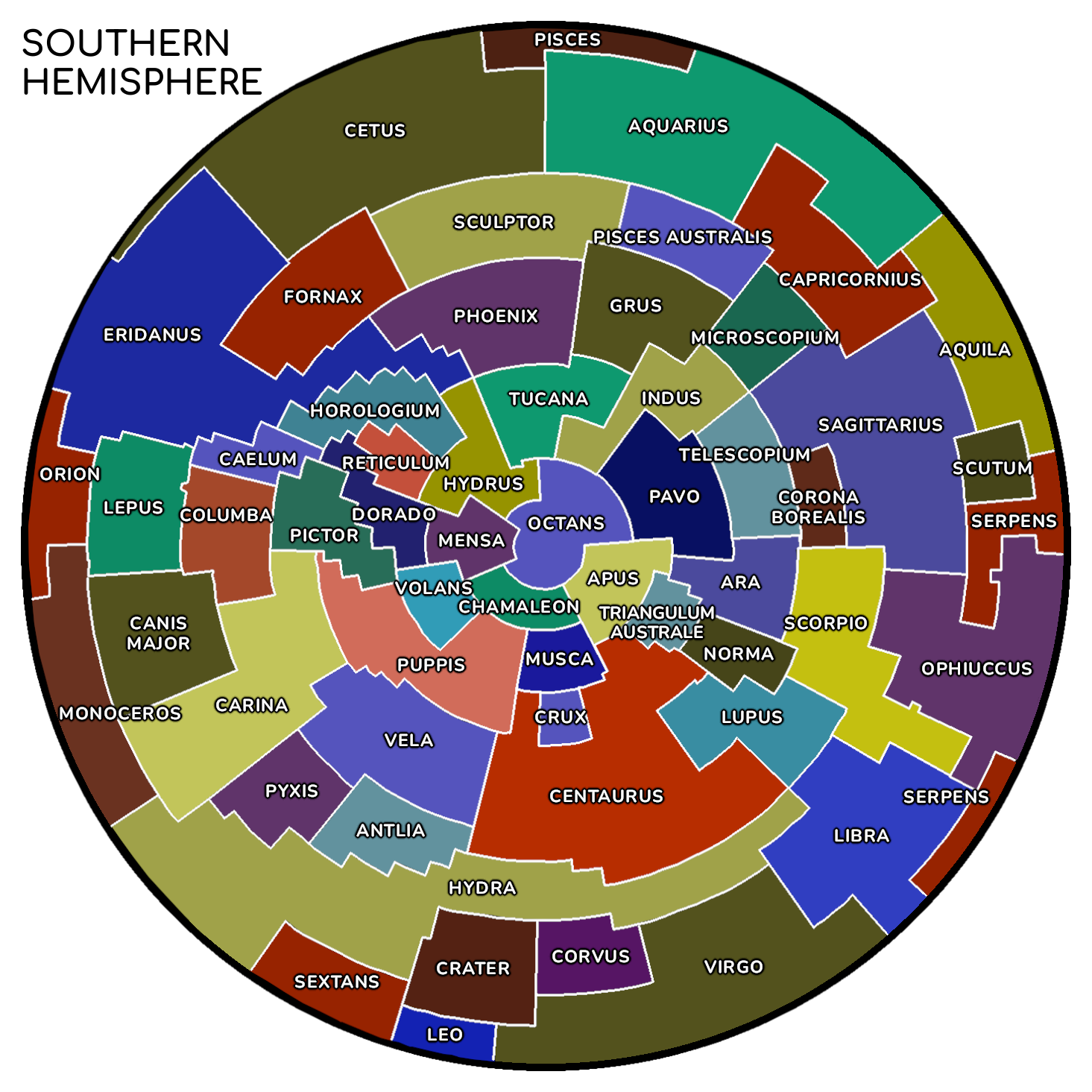

Touch here to visualize planispheres (arbitrary colors). Then touch them to see stars and patterns (magnitude lower than 3).

V. Links of interest

Atlases

The original works of cartographers mentioned in this article are available as digitilized documents in online public libraries. The viewers include descriptions of books (in Latin language) and high quality zoom viewing, with option for free downloading. Links at the bottom of each block. Some of the images are courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

Ian Ridpath's website

A website to take a path to the history of catalogues and atlases, referring to authors, origins and the way charts were made. Of an easy and quick reading, it includes most of the links found in this article, along with the mythological stories related to constellations. It also mentions Chinese constellations, with links to deepen more into them.

The Book of Fixed Stars

The Arabian astronomer Ἁbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī (903–986) added over 40 stars to Ptolemy's Almagest from the observatory of Shīrāz Persian city (29.6°N, Iran). His book Kitāb Ṣuwar al-kawākib (al-thābitah) also updated the locations mentioned by the Greek one although he didn't take new notes but made calculations based on the precession of equinoxes. He drew each constellation twice, with no coordinates, from both terrestrial and space perspectives.

More about cartographies

PhD. Filosophy thesis by Adèle Lorraine Wörz (2006) in Oregon University, entitled "The visualization of perspective systems and iconology in Dürer’s cartographic works: an in-depth analysis using multiple methodological approaches". It describes different methodologies for a critical appreciation of the history of cartography as well as the arts history. Next, it reviews Dürer's works by looking for meanings, conditionings and different kinds of subjective expressions at the time of considering spatial relations, perspectives, projections and iconology in his artworks. The document is of general interest and publicly available online for downloading (.pdf).

Comments

Join and leave a message. I always answer personally, and as soon as possible.